A Cry for Justice

Prison: The System That Thrives

When Cannabis is a Crime

Written By: MICHELLE LHOOQ

It was a sweltering afternoon, mid-June in L.A. when the visionaries behind the social impact cannabis brand 40 Tons arrived at Hiii HQ. Corvain Cooper, Chief Brand Ambassador, and Anthony Alegrete, COO, were cordial and upbeat, decked out in a stylish array of 40 Tons merch. They were followed close behind by Loriel Alegrete—CEO, Co-founder, and wife to Anthony—along with their young daughter. When Anthony turned to shut the door behind them, I caught sight of the words emblazoned on back of his shirt: “BUY WEED FROM WOMEN / LEGACY OPERATORS / BIPOC BUSINESS OWNERS / PAST CANNABIS CONVICTED / NOT TASTELESS RICH MEN.” It might as well be the 40 Tons slogan.

The idea for 40 Tons was hatched by Corvain, Anthony, and Loriel as a launchpad for their collective freedom. Just three years ago Corvain was in jail, serving a life sentence for a non-violent cannabis conviction. As cannabis is legalized across the U.S., there has been a mounting sense of injustice that thousands of mostly underprivileged Black men are still sitting in jail while stockbrokers and corporate big-wigs rake in millions. Capitalizing off this growing political awareness, various brands approached Corvain, trying to use his likeness and story for their own means. So Corvain reached out to Anthony, who he had known since high school. He was a fellow weed-hustler who had also done time for a cannabis-related conviction. More importantly, Corvain knew that both Anthony and Loriel had experience in the corporate world. In 2020, the three friends decided to create their own cannabis brand so that they could control the narrative, and make sure that any money raised went to Corvain’s liberation.

At the Hiii office, Anthony and Corvain sat down at a table with me and shared their life stories for this interview in between shooting off work texts on their phones. (“Sorry,” apologized Anthony sheepishly. “We’re always working.”) Loriel watched the two men from the couch, holding her young daughter’s hand. Suddenly, Anthony’s phone rang with a collect call from Edwin Rubis, who is serving a 40-year sentence for a non-violent cannabis offense. “Edwin is calling!” Anthony told Corvain, who grabbed the phone and greeted the person on the line like an old friend. Rubis is one of the prisoners that 40 Tons is working to help free, and he called to discuss the book they’d been collaborating on. Corvain’s eyes shone with optimism as he spoke to Rubis. “I’ve gotten over six calls just today from people who are in prison,” he later told me. “Sometimes they just want to catch up. They want their joy back. So yeah, I tell them—your faith has to be stronger than a life sentence.”

The call from Rubis was a stark reminder of an alternate reality that Corvain could have been stuck in, if he hadn’t received a one-in-a-million miracle: a Presidential pardon for his crime. When Corvain was in jail, the 40 Tons team collected thousands of signatures, networked with other cannabis industry insiders on apps like Clubhouse, and set up media appearances for him. This public momentum eventually turned Corvain into an ambassador for the cannabis social justice movement. “It was like managing Britney Spears,” Anthony joked about Corvain’s rising star. Their hard work eventually allowed Corvain’s case to reach the ear of the President, who granted him clemency and the right to walk free.

Today, 40 Tons aims to “bridge the gap between corporate and culture,” as Loriel put it. That means partnering with some of the biggest multi-state operators in the cannabis game to create social equity programs and sponsorships where money is given back to the communities that have been harmed by the War on Drugs.

In addition, 40 Tons also hosts career fairs where ex-cannabis convicts can meet recruiters at companies like Curaleaf, Verano, GTI Grows, Woah Flow, and Acreage Holdings that are looking to give those who have been screwed over by the system a second chance. And of course, since no cannabis-related company is complete without something for the stoners, 40 Tons also carries their own line of weed gummies.

Ultimately, their work at 40 Tons is about helping them make meaning out of the cycles of incarceration, broken families, and financial hardships that have dogged not just their families, but their communities and the generations before them. Breaking the patterns of trauma that we’ve inherited like cursed fates is better than winning the lottery; as Corvain puts it, it’s like a miracle that allows you to feel the grace of God. It is the best that any of us could hope for.

Here’s their story in their own words.

Anthony: Corvain and I went to Hollywood High together and just clicked as friends. We hung out together. We got in trouble together.

Loriel: I was dating Anthony, and we would all just hang out, go to the movies or the mall on the weekends. So yeah, we go way back.

Corvain: We started hustling and doing other hustles together.

A: We were just all hustling, hanging out, going to parties, kicking it, buying cars, jewelry. Well, everyone that we hustled with, they all smoked weed. We figured, if we could get some weed, we could just keep flipping it and flipping it. So we worked our way up.

L: Even though Anthony and I both worked hard to support our families, it still wasn’t enough. I was just thankful he didn’t run out. I’ve seen many situations where women have a kid, and the deadbeat dads go to jail or they’re nowhere to be found. So I was just grateful that he stuck around.

C: Eventually, we had to venture apart. This childhood friend I was working with came up with this idea to send crates of marijuana to Charlotte, like 300 pounds at a time. But he’s acting flagrantly, and he brings all this heat. The government eventually gets him, and that’s how the conspiracy charges start.

A: That’s the unfairness of the justice system. You don’t just get in trouble for your own pounds, you get in trouble for everything the people you worked with got caught for. That’s how conspiracies work.

C: Conspiracy is the worst law in the world. Hearsay is admissible.

A: And Corvain got life in prison because of three strikes. The other two strikes were for a pound of weed, and codeine. That’s why it’s so unjust, because the three strikes law was supposed to be about violence, not drugs, but weed is one way to arrest people very easily and keep the jails full. And get you caught up into a system.

L: I also was so infuriated that Corvain got life. I just thought it was pure fuckery that they would give him such a heavy sentence. He’s the only son from his parents, and his daughters were really young when he went away. I felt responsible to help him and his family, whatever way I could.

C: My dad sold hard drugs, and my mom was on drugs. So growing up and seeing all of that, I was never going to sell those types of hard drugs to cause pain to anyone’s life.

L: It’s sad to say now that jail for my family was like the new normal. At one point, I had five family members in jail, calling collect to me. I didn't know anything else other than to support these men while they were in jail.

A: I get hit too with the same types of charges. I was selling weed, and I got caught with more money at the airport than I was supposed to have.

L: Anthony went to jail a month or two after I had given birth. So I was dealing with a newborn baby and toddlers, fighting postpartum depression, and overwhelmed with anxiety and sadness that I have to do this shit all alone once again. I went through this roller coaster of hating him, furious that he put me in this position and abandoned me. I had to support him while he was in jail, keeping the lights on, juggling the kids, the house payment.

A: I felt horrible about going to jail, because I didn’t want to leave my kids. There’s a lot of trauma when you go away that you have no control over. Years later, I got pulled over while I was driving with my kid. And he went berserk. He was like, “No, they’re going to take you again.” And dude, I went home and cried. I caused the pain for them, and it hurt. I'm already coming from a broken home, and I forced my wife into being a single mom while I was in jail.

L: I would just bawl my eyes out in the shower, because I figured I just came out looking wet, and no one knew that I had been crying. I had to bear it for the children. My mother was a drug addict in the 80s, when the crack pandemic was an epidemic, and I was raised by my grandmother and great grandmother, who were extremely strong women. That's probably where I drew my strength from when Anthony was in prison.

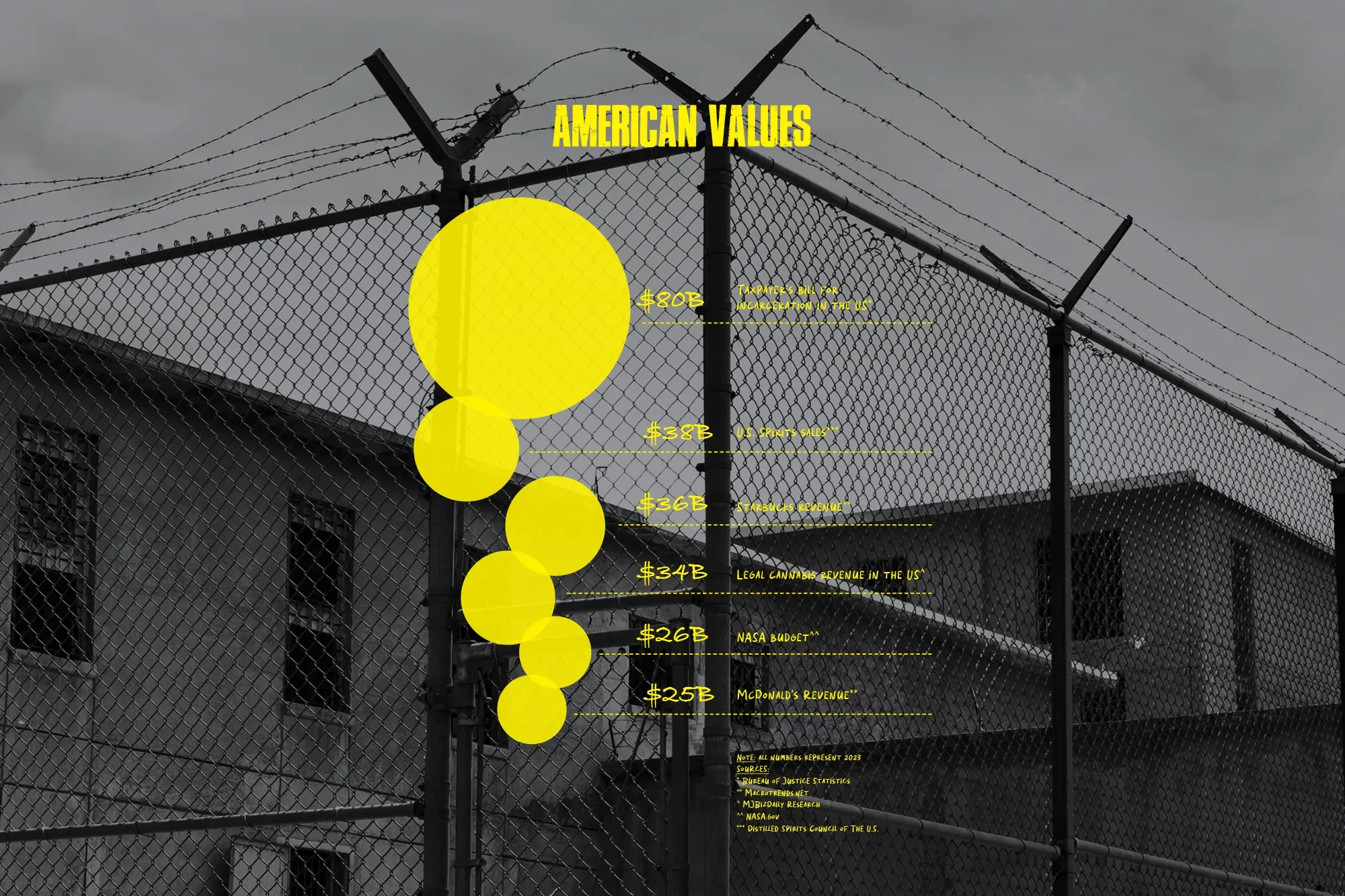

C: We’re coming from California, where weed is on every corner. It was on the stock market. So how come I’m doing time for something that stockbrokers are making billions of dollars from? This actually gave me hope. Especially with a life sentence. There’s no other drug that you could hope to be pardoned for in jail.

A: Listen, if you break the law, you go to jail. There’s no issues with that. But the punishment doesn’t fit the crime.

C: While I was in jail, I signed my rights over to Anthony. So we could start something for ourselves.

A: I saw that some people were using his story and his likeness in fundraising and not really giving him what we felt was fair. Everyone wanted to give 10 cents for every joint sold. And I was like, that’s bullshit. Give us the whole joint and let it be ours.

L: Jail was something that tore my family apart. But I was determined to make a difference. To try to create generational wealth, something that was not attainable in my family. Making different choices, smarter choices, doing things the legal way. So that this turmoil that I had been through, it wasn’t going to be in vain. It was going to mean something.

A: So three weeks before the President left office, Corvain’s lawyer wrote an op-ed in the New York Times, calling on him to let out cannabis prisoners. And there’s all this momentum, from mass letters, newspaper articles, and TV. There was this massive collective hope with the way the industry was moving that he could get out.

L: We had all that support, but we didn’t have a name for the brand. We were working with Corvain’s attorney, putting together the final touches of his clemency pack. And Corvain says, “I got the perfect name, let’s call it 40 Tons.” [Editor’s note: Corvain was charged with a conspiracy to traffic approximately 40 tons of cannabis.] Instantly the mama bear comes out of me. I was like, “No, no, no. I don’t want the government to think we’re spitting in their face, that we’re taunting them.” Because he’d applied for clemency already and got denied, and this was his last chance. And Corvain goes, “Listen, what’s the worst that they can do? They already gave me life.” Then I said, “You know what? You’re right. It is 40 Tons.”

A: I didn’t know if he was going to get out. I took the risk and flew out to the middle of nowhere in Louisiana, got a camera guy, and drove up to the jail. I said, it could go two ways: either he’s going to get out, and I’m gonna record the process. Or he’s not, and I’m gonna stand in front of the jail and picket, tell the story, and continue fighting.

“...They want their joy back. So yeah, I tell them—your faith has to be stronger than a life sentence.”

- Corvain Cooper

C: It was 11PM at night. We were watching CNN in jail, and it had the ticker at the bottom with the names of people that are getting clemency. But they still hadn’t said my name. So I’m like, fuck it, I guess I just had the biggest push, and I don’t know if I can ever even get a push like this again. So I wake up the next morning, and get suited up for being in prison for the rest of my life still. And we usually get handcuffed to go to the showers. But next thing I know, someone unlocks the doors. You can’t unlock the door—that’s a breach of security at a federal maximum security prison. And they said, “You’ve got five minutes, pack your shit up, you're out of here.”

So I’m knocking on the doors of everyone’s cells, giving away my stuff. Everyone’s screaming. And I’m yelling, you could do this shit. Because other people are in there for life too, right? So I’m like, don’t give up, really have faith. I was right in here in the belly of the beast with you, and I’m about to walk right out the front door. I get downstairs, and I’m crying to my mom on the phone. She’s like, “What are you crying for? Anthony called me last night, and he’s outside to pick you up.”

A: You can get knocked out real quick, worrying about hope. But in this particular case, we had to. Because we could put all this energy into building this business, and then he never comes home. And it never really gets off the ground. But it did.

C: We flew back to L.A. and the pilot announced it on the plane to everyone. When we got to the airport, there were newscasters already there. I did a press conference, then went to go see my kids. The newscasters followed us to film me seeing my kids for the first time. My family was outside when I pulled up, and I hugged my kids and told them I wasn’t gonna leave them again, that we were gonna be together forever. Then I actually fainted a bit, and people picked me back up. I was just in a twilight zone, like things were unreal. I was also just overwhelmed with happiness.

L: Now, as a social impact cannabis brand, I feel like we’re somewhat of an octopus with all the tentacles out there, trying to help the community and individual folks, assisting them in getting into an industry that they were taken away from. I want to be able to help women who were just like me. Or who can’t get a job because they have a criminal record.

Social equity is sort of a buzzword. It means something different to each person you ask. On a corporate level, it means what percentage are you going to give back into the community? Just tell me the number, and that'll be that. But for us, it means, how can we visit a jail? How can we accept collect calls from the folks that we're supporting? It means so much more than just that percentage, because that percentage does not put food on the table for the daughter or son of the guy who's serving a life sentence. For us, it means so much more.

Michelle Lhooq is a music, sex, mushroom and cannabis writer who has written for the LA Times, New York magazine, FADER, and Teen Vogue. She was the music editor for VICE. She is the author of the book Weed: Everything You Want To Know But Are Always Too Stoned To Ask.

"Send Me a Letter"

While legal cannabis flourishes worldwide, not everything, or everyone, is experiencing the joyous high. Meet Edwin Rubis. Rubis is 23 years into a 40-year sentence for a non-violent marijuana crime. While some non-violent marijuana prisoners have been pardoned, Rubis is still a victim of the unjust American prison system. However, with the help of people sending him supportive messages through The Last Prisoner Project, Rubis keeps up hope that he will one day be free.

The Last Prisoner Project was founded in 2019 out of the belief that no one should remain incarcerated or suffer the collateral consequences of offenses that are now legal. They brought together a group of justice-impacted individuals, policy and education experts, and leaders in the worlds of criminal justice and drug policy reform to work to end the injustice that is America's policy of cannabis prohibition. The team’s goal is to free the tens of thousands of individuals still unjustly imprisoned and to create front-end systemic reform in our criminal legal system.

However, Rubis isn’t idly waiting around. He is making the best of his situation. He’s received a master's degree in Christian Counseling and is now working on his doctorate. “I consider myself motivated, honest, positive, and always willing to go the extra mile to help others,” he said. “I'm interested in establishing friendships with open-minded, empathetic, positive people who see the glass as half full.”

Rubis asks this: Send him a letter and allow him to be a positive influence in your life.

“Hope to hear from you soon,” he says.

Learn

American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment, By Shane Bauer

With the last decade’s explosion of cannabis legalization, sometimes it is easy to forget that our prison system needs serious reform—especially for people convicted of possession of cannabis. In one of President Barack Obama’s favorite books, Bauer pulls off a heroic undercover job with style, hard truths, and plenty of head-scratching anecdotes. How did he do it?

Ten years ago, Bauer was hired for $9 an hour to work as an entry-level prison guard at a private prison in Winnfield, Louisiana. An award-winning investigative journalist for Mother Jones, he used his real name; there was no meaningful background check. Four months later, his employment came to an abrupt end. But he had seen enough to write a page-turning book exposing the corruption, immorality, and myriad of abuses in the private American prison system. Nearly every page of this tale contains examples of shocking inhumanity.

American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment was a very personal book for Bauer. He was held in an [Iranian] prison for two years, so he knows what it feels like to be on the inside, yet he brings to the text a journalist's purview and draws a direct line between American slavery, the founders of the prison corporations, and the job he was hired to do.

Read

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, By Bryan Stevenson

Quickly turned into a movie starring Jamie Foxx and Michael B. Jordan, Just Mercy is a potent story of exposing our broken justice system by someone who knows it inside and out. Stevenson, the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, and a professor of law at New York University Law School, has helped free dozens of condemned prisoners and has argued five times before the Supreme Court.

In the vein of To Kill a Mockingbird, Just Mercy goes where no book has gone before when it comes to telling the inside story of the broken justice system. However, every page is filled with hope and salvation. Stevenson has been called “the American Nelson Mandela” for fighting judges, prosecutors, and politicians for decades on behalf of the poor, uneducated, and desperate.

Just Mercy reads like a memoir; you’ll find yourself cheering for the fearless author and his passionate activism with every flick of the page. The Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Desmond Tutu, said of Stevenson: “He’s a brilliant lawyer fighting with courage and conviction to guarantee justice for all. Just Mercy should be read by people of conscience in every civilized country in the world to discover what happens when revenge and retribution replace justice and mercy. It is as gripping to read as any legal thriller, and what hangs in the balance is nothing less than the soul of a great nation.”